ESSAY

By Sarker Hasan Al Zayed

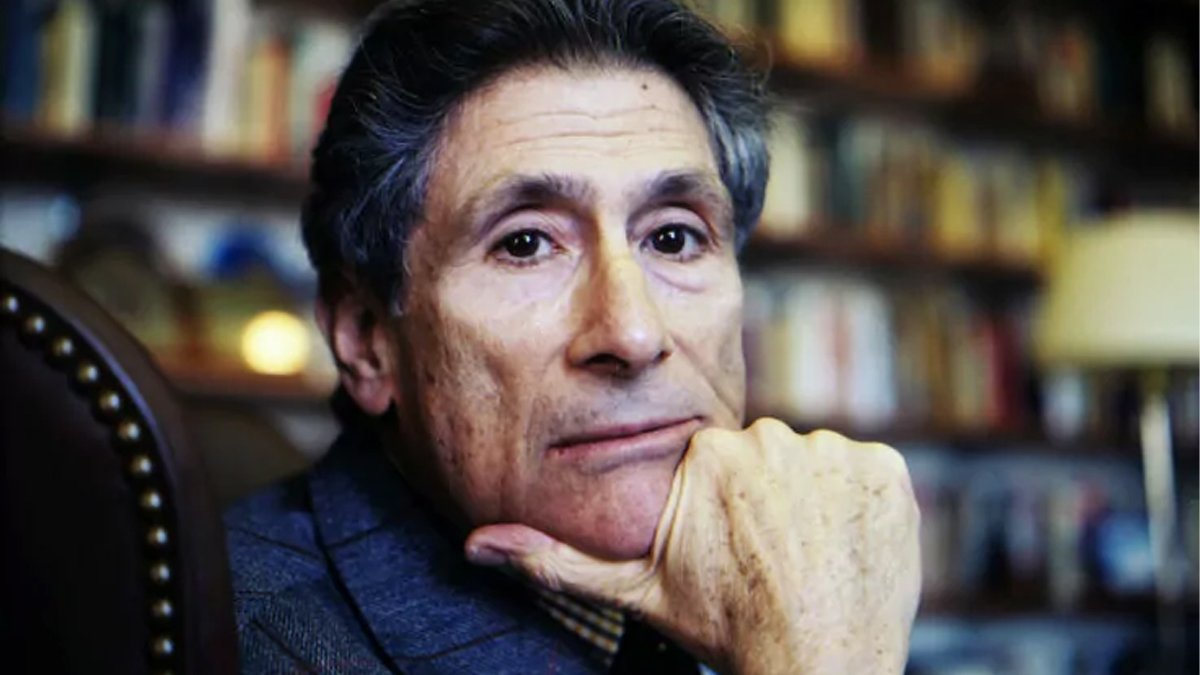

The day eminent Palestinian-American critic Edward Said turned 50, he was so upset that he declined to step outside of his New York City apartment. Gayatri Spivak, renowned scholar who was one of Said’s close friends back then, had travelled all the way from another city to NYC, hoping to take her friend to lunch. When she entered, she saw Said’s wife Mariam in the kitchen, preparing a meat dish. With Said declining to go out for dinner with her, Mariam had set herself to the task of cooking. “See if you can get him to go to lunch”, she told Spivak. “He is so angry at being 50 that he refuses to go to dinner with me.” The astute feminist, unable to convince her friend to bulge, eventually left after exchanging pleasantries with him. She was to have lunch of course, but alone.

The reason why this episode—which appears in Spivak’s commemorative essay titled “Thinking about Edward Said: Pages from a Memoir”—strikes me as compelling is because, in it, I noticed Said’s almost childish expectation to stave off finitude, death. It seems as if he fancied that time would slow down for him, allowing him to savour the life in which literature, music, and political activism featured prominently.

As I keep thinking about Spivak’s reminiscence of Said, I realise that the latter’s juvenile despair for ageing is more symptomatic than it appears at first look. For Said, life’s beginning, its continuity, and its closure were not just mundane biological phenomena but also philosophical conundrums. One has to thumb through the pages of his second book Beginnings: Intention and Method (1974) and posthumously published On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (2006) to understand how much significance he attached to life’s gradual unfolding. Yet, in a fundamental way, the force that steered Said’s intellectual pursuit forward was not just the aesthetics of living but also defiance.

In order to understand how Said turned defiance into his philosophical cornerstone, one has to take a close look at his intellectual morphing. He was born into an affluent Palestinian Christian family and went on to receive education from some of the most prestigious institutions in the world including Princeton and Harvard, institutions that instilled in him western liberal values. His happy settlement in that tradition hit a fundamental crisis in 1967, when Gaza Strip and West Bank were annexed by Israel, prompting Said to feel distraught and uprooted. Reminiscing how that event had upended his life, Said wrote the following in his memoir Out of Place (1999): “For me it seemed to embody the dislocation that subsumed all the other losses, the disappeared worlds of my youth and upbringing, the unpolitical years of my education, the assumption of disengaged teaching and scholarship…I was no longer the same person after 1967.”

The occupation of Gaza and West Bank changed Said’s personal and academic prerogatives, compelling him to lend his voice to the Palestinian liberation movement. The years that followed saw him veer further and further toward anticolonial and anti-imperial politics. Even Said’s purely aesthetic contemplations, his writings on style for instance, could not free themselves from the arching shadows of his political defiance. Beethoven’s atonality for Said became a tell-tale sign of the musician’s aesthetic belligerence, resisting bourgeois need for harmony. Adorno’s impenetrable sentences portended for him the signs of resistance against totalisation. Even Erich Auerbach and Julien Benda—both conservative figures—were in Said’s estimation anti-authoritarian figures, marginal thinkers swimming against the dominant current. However, he also continued to pay homage to revolutionaries and anticolonial thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci, Frantz Fanon, Amilcar Cabral, C L R James, Eqbal Ahmed, Raymond Williams and others, familiarising his American students to these figures.

The epistemic break in Said’s oeuvre, if there is any, must be traced in the distance between his first two books and his third—Orientalism (1978)—which changed the manner in which literary criticism was carried out in the academia at that time. Orientalism is by far the most influential of Said’s works; it is, also, his most vilified one. What is remarkable about this work is the passionate energy with which Said declares the whole of Western canon culpable of producing a binaristic discourse about the non-West. This is why, despite its anchorage in literary analysis, Orientalism reads like a political treatise, more a product of passion than a fruit of precision. Barring a few in the last decade of Said’s life, almost every book that Said has written since Orientalism displays similar argumentative fervour. The overlapping between literary criticism and political activism, which were his hallmarks in the 1980s and early 1990s, played a significant role in establishing postcolonial studies as an important branch of knowledge in academia. One cannot overestimate the role that Orientalism played in creating a global platform for the academics from the global south.

Beginning from the middle of the 1990s, Said’s interest in colonialism and imperialism began to blossom into an inquiry into the subject who embodies the trauma of displacement: the exiled. Both Representations of the Intellectual (1994) and Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (2000) are meditations on physical and intellectual exile. Sources of some of Said’s most brilliant essays, the chapters comprising these two books exude a sense of weariness and a note of vulnerability, elements that are rarely found in earlier books and essays.

The new century forced Said to come to terms with the growing tide of Islamophobia in the West in the wake of September 11 terror attacks. Debilitated by the stubborn persistence of leukaemia on the one hand and hounded by the media that sought to portray him as the “voice of the terrorists” on the other, he defiantly ignored the call to become a part of what he saw as the clash between fundamentalisms. He maintained his distance from the passionate aggression of both, while also asserting his powerful voice through a series of newspaper articles, mostly in Arabic. Although born into this language, Said lost his ability to write in it because of its disuse. In his 50s, he undertook the initiative to relearn how to write in his mother tongue. Wary of the narrowness of the western print and visual media and betrayed by some of his liberal friends in the academia who had suddenly turned against the entire Muslim population, Said defiantly ignored both as he continued to warn his predominantly Arab audience against the dangers of demonising the other.

The two books that Said completed before his death, From Oslo to Iraq and the Road Map (2004) and Humanism and Democratic Criticism (2004), exemplify Said’s ethical position against the Manichean discourse of “the clash of civilizations” that the extremists from both sides of the equator have wrought. Conscious of our collective precariousness and familiar with the shared life that people from different parts of the world live, he constantly reminds his readers that there is little to gain from a fractious world engaged in a life and death battle. In Humanism and Democratic Criticism particularly, Said straddles both western and non-western thought to argue that we live in a shared world and our intellectual inheritance cannot be entirely attributed to a singular source or culture.

My reading of Said convinces me that we have failed to do justice to his extremely vibrant and rich body of work. I have seldom come across academics who have read both Beginnings and The World, The Text, and The Critic (1983), both brilliant philosophical readings of literature. Nor have I seen our public intellectuals seriously engaging with his passionate and polemical works such as Covering Islam (1981) and Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims (1979)—works that attest to the limits and possibilities of Said’s political visions. It seems as if our neoliberal academia, after taking advantage of the polemical rigour of Orientalism, has characteristically abandoned him altogether, leaving his books to desiccate in the cold corners of university libraries.

Ours is a dark time—the era of global fascisms, fractious politics, and corporate monopoly. Faced with another conflict that threatens to erupt beyond the border, I look for Said for wisdom and insight. I see no one. Outside the cool late-October breeze blows quietly. The sky is dark. The half-blinking stars above timidly whisper: “November’s arrived!”

Author is Associate Professor at Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB). He is the author of Allegories of Neoliberalism: Contemporary South Asian Fiction, Capital, and Utopia (New York: Routledge, 2023).