Tuesday, June 25, 2024

Year : 2, Issue: 25

Sarzah Yeasmin

Police officers are often one of the first responders to an emergency. The public places a high social value and trust in their police as they have an obligation to protect. But the acts of gross police misconduct provoke fundamental questions: what if we need to be protected from the supposed protector? Do police officers serve the interest of the public? The issue of police brutality has gained more global traction in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. Yet many communities deem the issues of police violence to be a fringe issue that does not affect them directly. When injustice is part and parcel of the system, it is inevitable that it will manifest on our doorsteps and in our homes. Police force is ultimately an expression of state power and coercion.

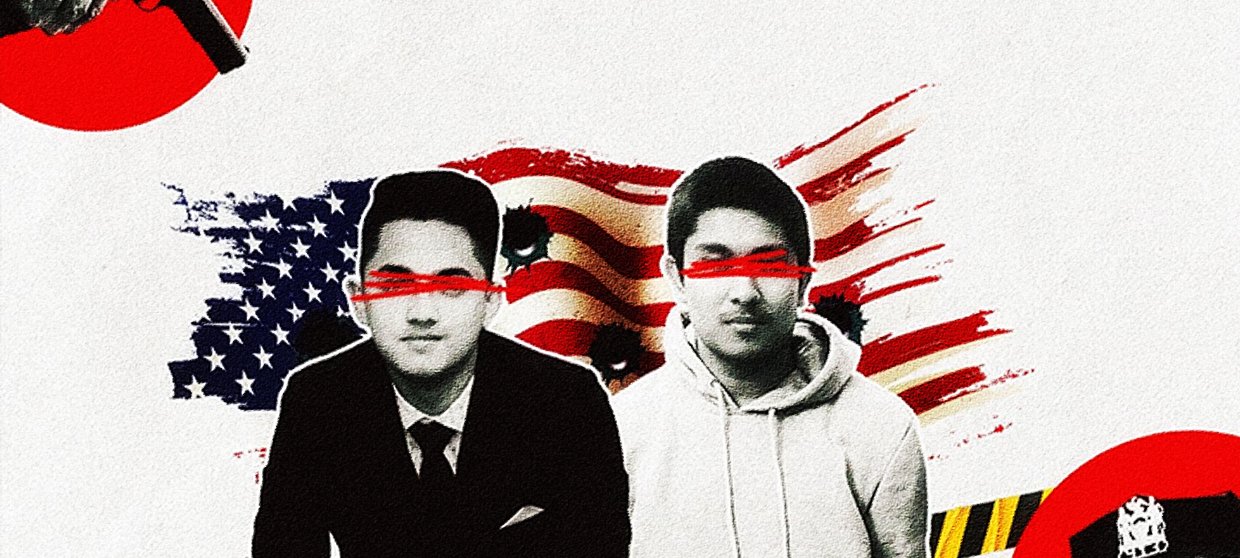

The police killings of Win Rozario and Sayed Faisal, Bangladeshi American youth, have been devastating for the diaspora. In both incidents, killing came as a response to a mental health crisis. Both Faisal and Win were shot as a response to non-criminal calls, when they needed help. The instances of non-criminal domestic disturbance calls ending in police killings are numerous. The American Public Health Association posits that police violence limits the minority community’s ability to achieve good health outcomes. The rampant and poignant crisis of police killings is a case of double jeopardy for the Bangladeshi American community: the Bangladeshi community’s help seeking behaviour is limited as mental health and help seeking are generally discouraged and stigmatised in a system that is disinclined to provide social support and health services particularly to communities living on the margins.

Shahana Hanif, the first Bangladeshi American member of New York City Council and a leading progressive voice in the community, mentioned how there are many Bangladeshis serving the law enforcement establishment at different levels and before police killed Win, there was a dearth of critical discourse on police violence on minority communities. She mentioned that police officers are trained to de-escalate but they continue to harm communities of colour. The crisis for the community is intensified further when the city continues to cut funding for social services and go above and beyond to fund the police.

Bangladeshi Americans make up one of the fastest growing low-income communities in cities like New York. The long history of documented immigration of Bangladeshis go way back but the recent profile of the Bangladeshi migrant community is defined by the migration pattern starting in during the third wave of Bangladeshi immigration post 1981, when more working class Bangladeshis started migrating to major urban centres. This community experiences acute health disparities and neglect, coupled with high rates of discrimination and low social support—added to the stressors of being in a recently settled immigrant household. Lack of meaningful access to resources also derails help seeking in the community. Win’s and Faisal’s deaths should not be moments of reckoning for the Bangladeshi community only, but for the whole of the US, as the processes that led to these heartbreaking outcomes sit on matrix of systemic bias, neglect, discrimination, inequality, and model minority mindset where “positive” stereotypes of Asians as hardworking, docile and apolitical migrants pushes the South Asian and Bangladeshi diaspora in the United States to excel at the expense of meeting their needs.

The negative verdict on Faisal’s case is not surprising: a Massachusetts judge found that the officer was justified in shooting Faisal. Oftentimes the rationale of self-defence, police being responsive to their training rules, overvaluation of police witness and narrative over non-police witness play pivotal roles in decision making. Bringing a criminal charge resulting in an ultimate criminal conviction in cases of police killings is an uphill battle—with bottlenecks on every step of the legal system that confirm systemic bias and provide broad impunity to the police. Standards of criminal law dictating use of lethal force by police are ambiguous and tilt towards favouring the law enforcement establishment. Prosecutors and district attorneys are usually disinclined to charge or convict their own police officers and place more faith on the police narrative as they are reliant on the police for their work.

Police also receive privilege under criminal law as they have special justification for use of deadly force. There are also broader political and cultural issues around law enforcement, guns and safety advanced by special interest groups, police unions and politicians that need to be considered to comprehend the intricacies around police violence. If the police officer “reasonably” believes that use of lethal force must be used to prevent harm to self or others, then that is seen as enough of a justification for violence resulting in death. The cost of police killing is not as well documented, but it is mainly borne by the victim’s family and the health care system, in some cases the city government if the case reaches a settlement—very small percentage of claims ever reach settlement. Killing comes at a minimal cost to the police department as many cases are squashed in the administrative reviews and procedures. The officers responsible for killing are usually put on paid administrative leave or modified duty and are eventually reassigned. If there are any sanctions on the police officer, they are usually recorded as disciplinary expenditure on the police department budget—not categorised as cost related to the use of lethal force. Regardless, police departments continue to get funded without much promise for change. Only a handful of major US cities have signed consent decrees—a legally binding performance improvement plan.

Law enforcement officers can only use life-threatening force when responding to a threat or use of deadly force. Win had a pair of scissors and Faisal had a knife. Would holding a knife or a pair of scissors in the presence of police officers armed with high calibre weapons count as using deadly force? What relative capacity of harm do these weapons possess compared to a gun used by a trained police officer with far more capacity for harm and damage? Knife is considered to be a weapon of deadly force under the twenty-one-foot rule which posits that the holder of a knife can cover a distance of 21 feet in the time it takes to fire two shots. All such minute technicalities and rules stand in favour of the police officer who decides to use force. Did Win and Faisal’s reaction, triggered through unaddressed mental health issues, constitute grave danger for the police? Did the victims substantially provoke police’s use of lethal force?

Pointing a weapon or something that reasonably looks like a weapon is seen as one of the most common triggers for the police to use their firearm. One detail about police misconduct is important to note: any police misconduct is counted as a single act of applying deadly force—if the first shot from the police’s gun is seen as justified, then that covers all subsequent shots and use of force and justifies any additional aggression. Liam McMahon shot Faisal a total of six times—and regardless of how many times the police would shoot, if the first shot is concluded as a justified shot, so are all the shots, even though death rate is much higher in cases where multiple shots are fired. Number of gunshots has a predictive value for death. Therefore, there is no disincentive for the police officer to use additional force or shoot additional times that lead to deaths.

Recent innovations in monitoring police conduct are only making incremental and gradual changes. In my conversation with Tanvir Chowdhury, president of Bangladesh Association of New England, he mentioned how pleading for justice for Faisal pushed the Cambridge police to improve their policies, wear body cameras and led the city to consider alternate social service for emergency response. Regardless of minor innovations, issues of poor governance remain unaddressed, and the police continue to have major control over visual evidence. Public who film violence also put themselves at risk of being subjected to police misconduct—ultimately undermining non-police public witness narrative.

According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, the main reasons for the police wearing body cameras is to improve officer safety and reduce liability of police departments. However, small scale experimental studies have shown that the use of body cameras has the potential to improve police conduct. Video evidence has been pivotal for garnering public reaction, but it does not guarantee ease in bringing criminal charges or prosecution. Evidence would also not weigh in as much in instances where there are irregularities in disclosure. The bone chilling last moment of Win’s life has been recorded; the public can hear his mother repeatedly pleading to the police not to shoot her son. It is yet to be seen how public reaction and the video evidence of violence shapes the investigation and verdict in Win’s case, but it has the potential to boost and prolong the campaign for justice. It was only in 2020 that Section 50-a of New York City’s Civil Rights Law, which kept disciplinary records of police officers hidden from the public, was repealed after almost a decade-long fight. Any change is hard-won. While the avenue for criminal prosecution might be exhausted with the ruling in Faisal’s case, Tanvir sees possibilities in civil litigation. The way Faisal was portrayed in the media in the aftermath of his undue death, caused his family severe distress. It is critical to pursue justice in the face of this gridlock to continue to honour and humanise our people.

Should the police be left out of the public safety plan then? Officers receiving training in de-escalation are quick to resort to lethal force, would calling the police for help entail an inevitable deadly outcome? Police violence, brushed off as a non-issue for the Asian and Bangladeshi community in the US, has hit hard and hit home this time. For now, the only promise of change can be found in Win and Faisal’s families and communities that continue to fight for justice.

Author is a Boston-based Bangladeshi writer. She works at Harvard Kennedy School and is currently pursuing a micro-master’s in data and economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)/Views expressed in this article are the author’s own./Courtesy by The Daily Star