On a hot, sticky day in early October, 25-year-old Alesmar stood on a street corner in Manhattan holding her son’s hand.

Wearing a tank top, her dark hair bound up in a pink scrunchie, she did not want to share her last name. She said she arrived in New York at the end of April, after two months traveling by foot and bus from the port city of La Guaira, Venezuela, to the US border – a difficult journey marked by frequent setbacks.

Mexican regional officials kept forcing Alesmar and her kids back south, making Mexico the longest-lasting segment of their trip.

“It was especially hard in Mexico, where they grabbed us and sent us back,” she explained. Referring to Mexican states, she added, “State after state denied us permission to transit and sent us back in the direction we came from.”

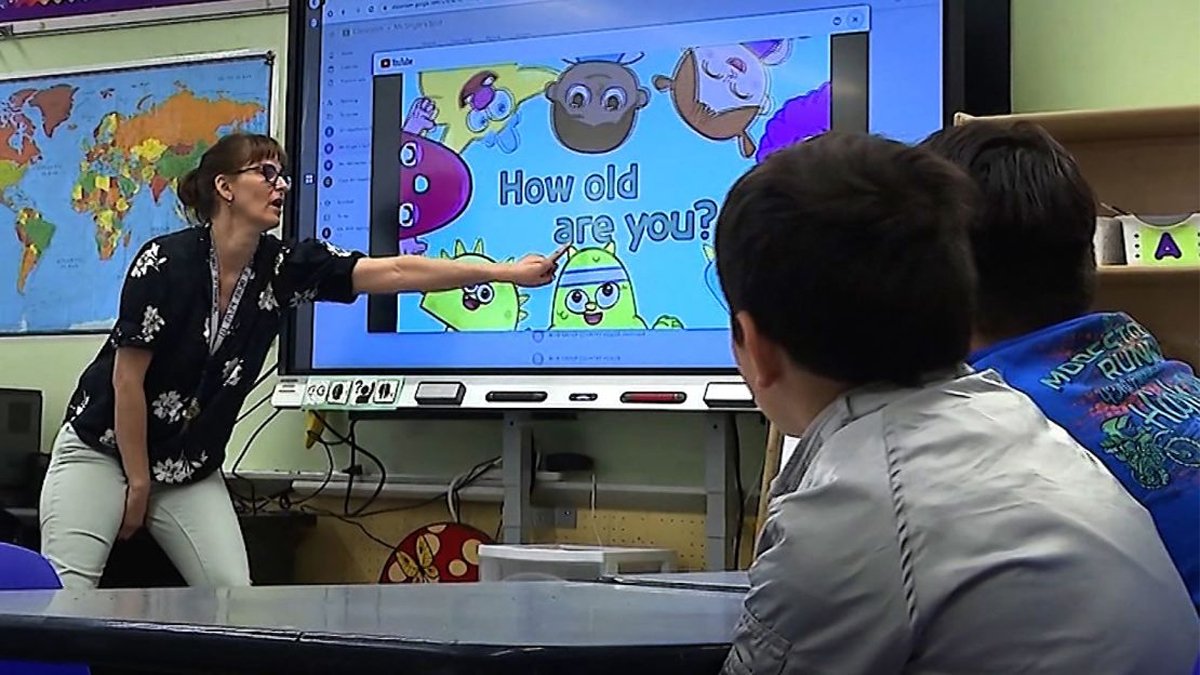

Eventually, Alesmar made it to New York. She is still living in temporary housing in Manhattan and her two young sons, ages four and eight, are enrolled at nearby Public School 111, where they are learning English and adjusting to life in a new country.

“It’s a new place for them, because of the language, but they’re doing really well,” she said. “I want something better for them, since we cannot achieve anything in our country.”

Alesmar’s children are among dozens of new students at the elementary school that has long welcomed a diverse student body, with children hailing from places like Ukraine, China and Tibet. Some 56 percent are Hispanic.

More than 120,000 migrants have arrived in New York since the spring of 2022. Many live in temporary housing – often hotels serving as shelters – and many are seeking asylum. The surge has added nearly 30,000 children to the city’s public schools.

NYC Schools Chancellor David Banks has said new arrivals will get “the best” the city has to offer, and since about 120,000 families left New York public schools over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, there is room for the newcomers.

In fact, P.S. 111 has not yet returned to its pre-pandemic population. Three new students enrolled the day CNN visited.

About 36 percent of the school’s roughly 400 students now live in temporary housing, compared to 10 to 20 percent of the student body in a typical year, according to Principal Edward Gilligan.