Tuesday, May 14, 2024

Year : 2, Issue : 20

by Mohammad A. Quayum

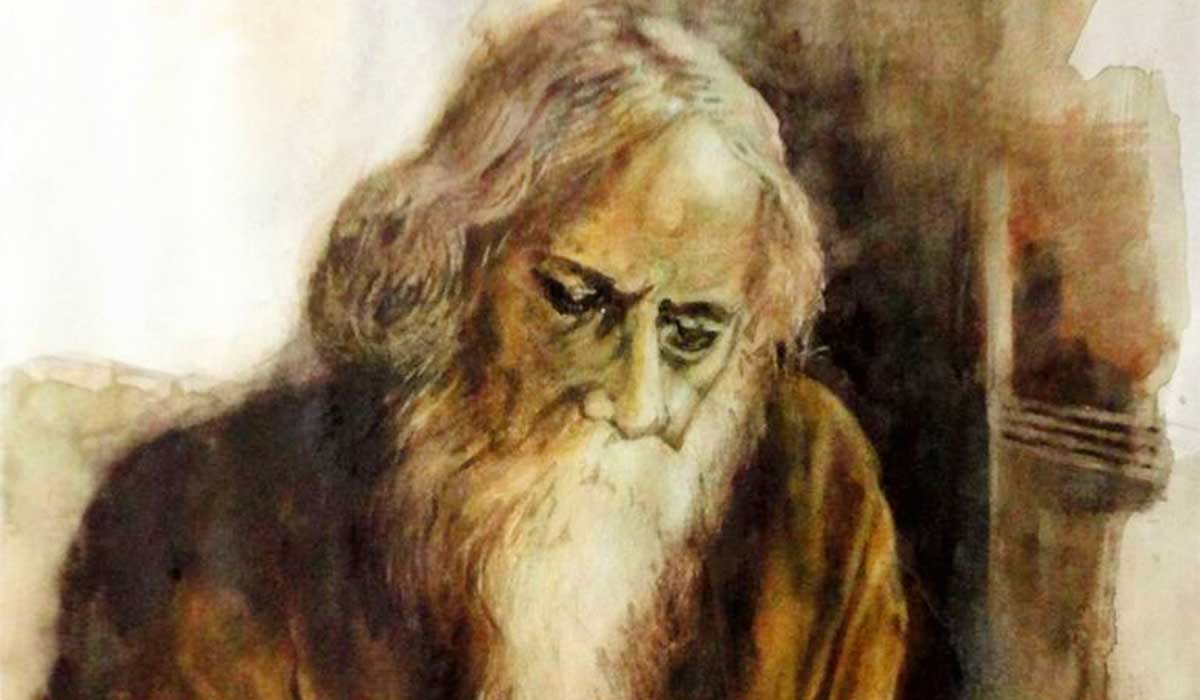

The English poet W.B. Yeats once expressed his profound admiration for Rabindranath Tagore, describing him as “someone greater than any of us”. Similarly, after meeting the poet at an event in Cambridge, UK, Francis Cornford, granddaughter of Charles Darwin, remarked, “I can now imagine a powerful and gentle Christ, which I never could before”. Despite such acclaim for his polymathic genius, Tagore often attracted broadsides from various factions, including, in his own words, “political groups, religious groups, literary groups [and] social groups”.

Some of this vitriol has come from his home turf, where several critics have accused him of religious bias, branding him a Hindu nationalist, a hierophant of a Hindu-centric India and a Hindu extremist who held an intrinsic bias towards Muslims. However, this view seems specious, given Tagore’s lifelong aspiration for global unity of humanity and engagement with Islamic culture and Muslims in a spirit of inclusivity and good fellowship.

A proponent of the principles of Advaita (non-duality of creation) and Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (the world is one family), Tagore rejected narrow-minded ideologies of all forms that restricted the individual’s personal growth and rendered them “unfit for citizenship of the world.” In Fireflies, he condemned sectarianism in a deprecatory trope:

“The Sectarian thinks

That he has the sea

Ladled into his private pond.”

Critics who accuse Tagore of Hindu chauvinism and antipathy towards Muslims fail to appreciate his non-traditional Hindu background as a Brahmo and his fiery critique of Hindu formalism in his work. They also overlook that Tagore made significant efforts to unite Hindus and Muslims to create a Mahajati in India. For example, he established an Islamic Studies Department at Visva-Bharati University in 1927 and a Chair of Persian Studies in 1932. He also admitted Muslim students, including the renowned writer Syed Mujtaba Ali, right after founding the university in 1921. Moreover, he maintained amicable relationships with various Muslim writers and intellectuals of his time, took compassionate actions to alleviate the hardships of his Muslim tenants in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) while managing their family estates, and publicly honoured the religion and prophet Muhammad in national media outlets on Muslim festive occasions.

In a lecture at Oxford University in 1930, Tagore explained that his sensibility was shaped by “a confluence of three cultures, Hindu, Mohammedan and British.” The influence of Islamic culture began on him early, as he was raised in a Persianate ambience, surrounded by Muslim food and dress. Many of his family members wore “Mussalman type of Achkan and Jibba”, and Tagore’s earliest surviving photo from age 10 shows him wearing a Jibba robe like Iranian royalty.

Tagore was born into a Brahmo Samaj family, a progressive Hindu sect founded by Rammohun Roy after being influenced by Islamic monotheistic ideals. Roy received his early education in a Muslim madrasa, where he mastered Arabic and Persian, enabling him to study the Qur’an, Islamic jurisprudence, Islamic philosophy and classical Sufi poetry in their original languages. Subsequently, he authored a long essay in Persian, “Tuhfat al-Muwahiddin”, in which he vehemently criticised Hindu idolatry and superstition, concurrently advocating their reform from an Islamic perspective. The movement’s reliance on the Qur’an and Sufi literature was so profound that a Brahmo missionary named Girish Chandra Sen was the first to translate the Qur’an into Bangla, who also used Sufi poetry to impart ethical and spiritual teachings to the Brahmo Samaj adherents.

Tagore and his father, Debendranath Tagore, were fervent champions of Sufi literature. Debendranath, proficient in Arabic and Persian, revered Diwan-i-Hafiz as a sacred book and recited it regularly as part of his midnight meditations. Influenced by his father, Tagore also became intoxicated with it. During his visit to Iran and Iraq in 1932, Tagore spent an entire week in Shiraz to honour the mausoleums of two eminent Sufi poets, Saadi and Hafiz, declaring himself a natural successor to these Sufi saints.

During his visit, Tagore profusely praised the Islamic civilisation in Iran and Iraq. In an address to the Armenians, he applauded Iran for its “message of brotherhood, of freedom, of federation in the task of establishing peace and goodwill”. He also lauded the people and lifestyle in Iraq, acknowledging how profoundly Islam and Muslims have contributed to the Indian civilisation. He urged an audience of Iraqi writers to send more people of faith to India to help alleviate its ongoing ethnic and religious feuds by uniting different communities under the banner of fellowship and love, transcending petty factionalism.

Tagore maintained cordial relationships with numerous Muslim writers and intellectuals of his time, including Dr Muhammad Shahidullah, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Kazi Abdul Wadud, Shahid Suhrawardy, Golam Mostafa, Jasimuddin, Syed Mujtaba Ali, Muhammad Mansooruddin, Bande Ali Miyan and Sufia Kamal. He invited Dr Shahidullah and Abdul Wadud to deliver lectures at his institutions in Santiniketan, appointed Suhrawardy as the Nizam Professor at Visva-Bharati and Syed Mujtaba Ali, who had a PhD from a German university, first as a professor of the German language and then as a professor of Islamic culture.

Nazrul was first introduced to Tagore by Shahidullah. At their first meeting, Tagore invited Nazrul to stay back at Santiniketan, but Nazrul, a maverick and a bohemian, refused to. However, he later became an enthusiastic exponent of Rabindra Sangeet. He also dedicated his anthology of poems, Sanchita, to “Poet-Emperor, Rabindranath Tagore”. In return, Tagore dedicated his dance-drama “Basanto” to Nazrul. After Tagore’s death, Nazrul became so distraught that he composed several poems honouring his icon, including the long elegy “Rabihara” and “Salam asta Rabi.”

All the Muslim writers in Tagore’s circle have paid glowing tributes to Kabiguru, but none more than Poet Golam Mostafa. He described Tagore as a Muslim at heart and stated categorically, “We did not find any hostility towards Islam in the vast literature produced by Tagore. On the contrary, there is so much of Islamic content and ideals in his writings that he can be called a Muslim without hesitation.”

Tagore spent 10 years from 1890 to 1901 in Shelaidah, Kushtia, looking after their family estates in East Bengal. During this period, he had the opportunity to engage closely with Bengali Muslim culture. His boatman and retainer, Abdul Majhi, and most of the 3000 tenants working on their land were Muslims. This daily interaction with Muslim families helped the young poet understand and appreciate their way of life and traditions.

Tagore’s respectful embrace of the Muslim community is evident in many of his works but most incisively in a letter written in 1931, affirming, “As far as the country itself is concerned… we cannot deny the fact that the Mussulmans are our close relations… I love [my Mussulman tenants] from my heart because they deserve it”. To mitigate their hardships, Tagore administered various measures, including reforming the estate judiciary system, establishing a bank, a school and several industries.

In 1935, Tagore wrote the Foreword to a book, A Simple Guide to Islam’s Contribution to Science and Civilisation, by Maulvi Abdul Karim. In it, he explained that although Muslims and Hindus have been living together in Bengal for centuries, they were still hostile towards one another because of their widespread ignorance and apathy towards each other’s culture. His solution was a mutually sympathetic understanding of their values and traditions and an enduring fellowship rooted in love, empathy and trust – a vision Tagore cherished and championed much through his life and works.

Author is a Flinders University, Australia, has published one authored, two translated and three edited books, as well as several articles and book chapters on Rabindranath Tagore.