Tuesday,

February 11, 2025

Year : 2, Issue: 24

FICTION

by A.M. Fahad

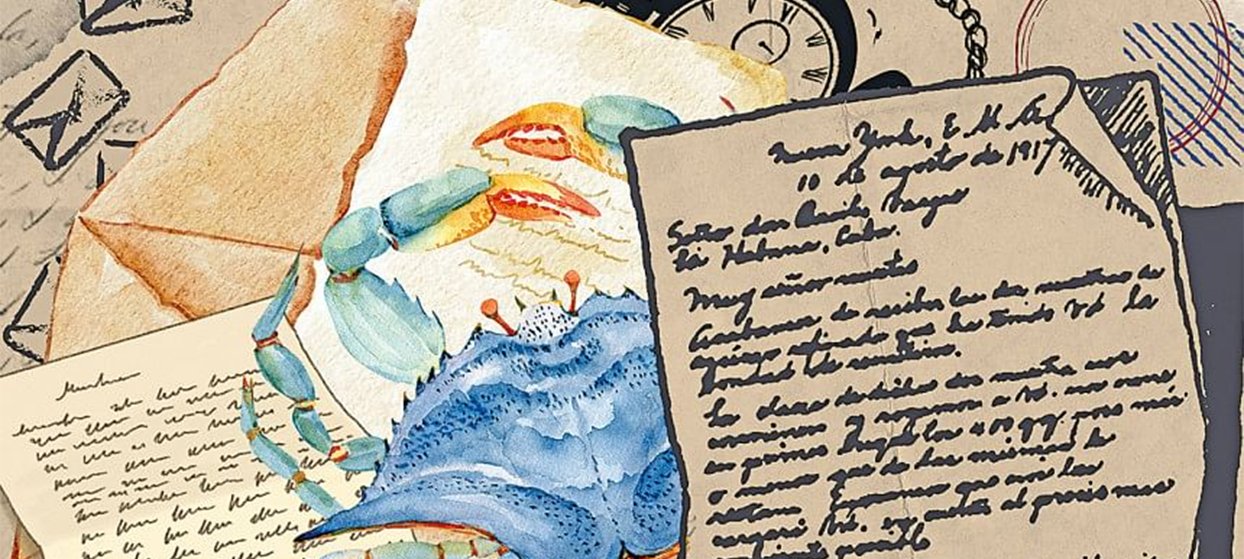

You tell me stories of the sea—of its waves, of how it speaks to you in a language only you can understand—whenever you write back to me. You’re a funny man. It seems you’ve developed a fondness for soft-shell crabs and Loitta fries. We miss you. Ma’s thyroid condition has worsened. We will go see Dr. Titu Mia next weekend. Everything else is okay. I hope you get to come back soon. Your son is growing into quite a rebel. He’s just like you. Please eat well. I will be waiting for your reply.

Ayman reads the last bit of the letter again and folds it with a sigh. He gazes intently at the sunset. It’s been almost 14-and-a-half months since he left home. As an independent journalist, he has traveled to many countries, seen many wars, and swallowed many of his emotions in the process of reporting and writing.

“It will keep the love intact! You won’t forget that you are stuck with me when the parchment reaches your hands, Mr Journalist,” Rity smiled as she folded his clothes 14-and-a-half months ago. She was talking about letters. She was always rather fond of letters because telephones are expensive.

Ayman was never ambitious about his work, but he never actively went against the idea of it. What he wanted to pursue, he felt—the feeling—had died by the time he grew up. He was nothing more or less than a doe-eyed child who grew bitter as he tasted the spoils of life. As bitter as the chalta fruit his father used to bring home, the scent of tobacco on his clothes, and the longing he felt for his approval of his little poems, left only with the memories of the hot anger and disappointment in his gaze. As he grew older, he found himself becoming more reserved about anything and everything the whole world had to offer him, except his now wife, whom he met during his time in university—the bicycle rides, the packageable picnics under mango groves, the dispensable dreams they would conjure under the soft shade of spring. And as most sons do, he loved his mother. ‘Sabr’ is Ma’s favorite word. “You will see the world. You will travel to beautiful places and forget about this place. Have Sabr. This will all be over when you’re old enough. You’re not old enough to take responsibility. And we could not survive without your father. Have Sabr. You’re an impulsive child. Don’t speak against your father if he says or does something. I have spent 26 years living this life. I have grown used to it. Have Sabr. It’s not the end. Have Sabr, because the Almighty has plans for everyone. Have Sabr, my love, because it’s only the end when you allow it to be the end,” his mother said to him in a locked room on a cool and breezy day, with his back still red from the backhands of Abba’s belt.

“Altaf bhai, my son will make the most beautiful cities,” announced his father when he was old enough to remember the conviction in his father’s gaze, but he didn’t have any intention of building cities. He disliked cities, swarmed by people, cesspools of vice. Growing up in Chittagong, his heart belonged to the mountains and the seas, but living so close to the scent of despair disillusions you of the veils of beauty. After traveling an hour from Khagrachari, he could see the camps and checkposts on the way to Sajek. As a teenager, he was fascinated by armed personnel gracefully flinging their weapons and making sure everything was okay. But the matter of things being okay or not was a matter that would be decided by some higher presence that eluded the human eye here. Were they protecting him, or were they protecting themselves from something terrible? But what is a more terrible thing for the gulp in someone’s throat than the truth?

His father served in the military. He enjoyed imposing authority, to which Ayman slowly exercised more and more defiance. He struggled to come to terms with the norms of discourse in his house. A place that turned all his propositions and questions to disrespect, a disrespect he struggled to understand, a term he was labeled that would slowly break all his patience. And it did, eventually, break all the Sabr his mother was piecing together bit by bit by bit. It happened on a warm summer morning. It was fast. It was loud. Words and fists flew everywhere. When the dust settled, he was still only a “beyadob”; but this time, he had his mother’s hand in his and a small bag of his precious things with him. He walked out of the door years ago, and he never went back. His father has a weak heart now, and Ayman sends him his expenses every month in a parchment, though he has no need for it; it is devoid of any semblance of love.

He folds Rity’s letter and gets up on his feet, walks 10 paces to find a clean and smooth rock to sit on, and he holds his face with trembling hands. Maybe he has turned into the opposite of what anyone had aspirations for. Maybe the world is a terrible place.

If there is beauty to be found in the world, he does not know of it yet. In 12th grade, he came across an excerpt by Ocean Vuong during one of his long escapades, “Let no one mistake us for the fruit of violence—but that violence, having passed through the fruit, failed to spoil it.” He fancied himself the survivor, the hard seed buried deep inside the fruit, obstinate in his defenses against the corrosion that surrounded his soft skin, attempting to spoil his insides. Maybe he got it all wrong, or maybe he got it right. Only his reflection in the water now can tell what he is.

In these 14-and-half months away from home, he has held his breath without pause. And maybe he keeps going from one place to another to find parts of his heart he has lost in the process of trading his heroes for ghosts. And maybe he should breathe, for if he does not breathe to live another day, there will be another story buried under the rubble of chaos and destruction, hoping the rest coalesces into a form of existence that one can tolerate, if not love—an acceptable way of living, he thinks. And so, he tosses a rock into the sea and gets up from the one he had been sitting on, Rity’s letter still folded in his hand. He must go back to his hotel and pack his bags. He must also buy a one-way plane fare now if he hopes to catch the last plane home; home, where his heart still remains.